Being a writer is an interesting job.

Some days, I have to dig deep into my soul to find a lesson worth sharing. Other times, those lessons drop straight in my comments section, fully formed and ready to go.

Take this week, for example. I made a little TikTok poking fun at NFL fans who booed Taylor Swift. Without getting too into the weeds, it was just a 15-second commentary on joy—on who experiences it freely and how those who don’t often find ways to mock the ones who do.

I posted the video, laughed a little, and moved on.

Honestly, it wasn’t that deep.

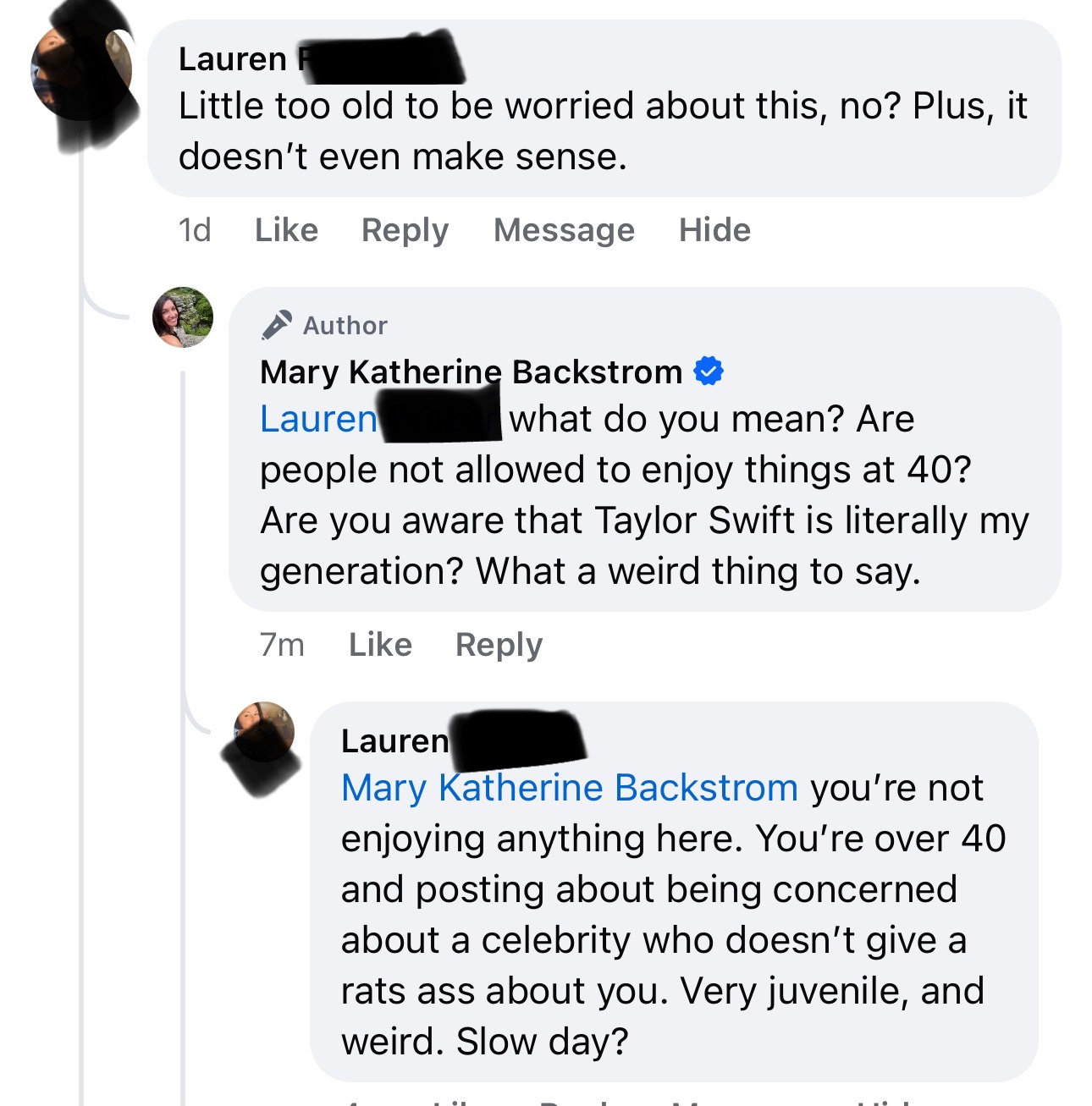

But apparently it was for Lauren, who came flying out of left field into my comments section.

Ole girl clipped every context clue on the way down before crashing headfirst into the point, leaving me a nasty comment about how I was “too old” to be making videos like this—the heavy implication being that I should follow somebody’s invisible rules and make myself smaller than I am.

Lack of self-awareness and incredible irony aside, here’s the thing: I know who I am.

I know that what I do is playful. I am fully aware that I’m a 40-year-old woman holding a phone in front of my face, adding music to my thoughts, and posting it on the Internet. It’s objectively a funny and ridiculous thing to do. I get that, one hundred percent.

There once was a time when comments like that stung—when I wasn’t so sure of myself, and it was easier to believe them.

Maybe you should be ashamed. Maybe you were childish. Maybe people are right to laugh at you.

But now I like myself, and that makes me see these commenters differently. What used to feel like valid criticism reads as grief.

And I don’t mean my grief.

I mean theirs.

Because the truth us, a person who can’t have fun isn’t a whole person at all. They’re merely a fraction of themselves, and its pretty to me the piece that is missing.

A child.

One who knew how to play, how to feel light, how to let go. And when people lose that piece, life starts to feel pretty darn heavy.

I remember what that loss felt like, and I remember when it happened to me.

I was in fifth grade, on the cusp of entering middle school, sitting in a crowded cafeteria with my mom and a hundred other parents and kids for the “Welcome to Sixth Grade” meeting. The room buzzed with nervous energy as we listened to the vice principal explain how life was about to change forever.

“You’re not just going to have one teacher anymore,” she said. “You’re going to have four. You will be responsible for knowing where these classrooms are. You’ll get a locker, and you’ll need to know the code. You’ll be responsible for keeping up with your schedule and responsible for all your books. Oh, and another thing…there’s no playground.”

I don’t remember what she looked like, but I remember that she felt like the mean headmaster from Harry Potter—the one who wore pink and giggled sweetly while crushing everyone’s joy.

My hand shot up.

“What does everybody do when they have time outside?”

She blinked at me as if I had just asked the most surprising question in the world, like it had never crossed her mind that someone might need a little clarification.

“They stand around and talk with their friends,” she responded, as if the answer was plainer than my nose.

As if my childhood wasn’t being snatched from me right there in a sad, dirty lunchroom.

But it was time to grow up, I guess

I was a sixth grader now.

My future spread out before me like a barren, soulless blacktop—a patch of gravel where I’d be relegated forever to stand around kicking cans, arguing with friends about whether or not it’s possible to kiss a boy who has braces.

I imagined this was what it felt like to be a 1950s dad, leaving the joy of childhood behind for a bleak future of grinding to provide for hungry mouths.

Gone was the freedom I found on the swing—the centrifugal pull, the way it hollowed out my stomach and made me feel like I was flying, toes pointed toward the sky while my heart soared, eyes burning from the wind.

It felt like a shitty exchange, but I figured I’d acclimate well enough.

A whole class of kids did every year.

So, I did what I was told. I took my place on that blacktop, gossiping with the other sixth-grade girls, pretending I wasn’t still longing for the playground.

And that year, something shifted in me. It felt like a break—small and quiet, but deep. I couldn’t quite name it then, but what I do know is that the world started to feel a bit heavier.

This was the first unwritten rule I had internalized. I was twelve, and playtime was over.

It sucked. And it would only suck a lot more the older I got, as the rules kept falling at me like bricks from the sky.

What to wear. How to act. What to say. Who I was supposed to be.

These rules followed me into adulthood, layering on top of each other until the joy I once felt seemed buried beneath the weight of it all. I was so covered up in invisible rules that they formed a wall around me—one I couldn’t move within.

To my deepest grief and utter relief, that wall came tumbling down in the form of a divorce—a complete collapse of everything I thought I knew about life and who I was supposed to be. It was the most beautiful hard reset one can experience.

I was given the privilege of rebuilding myself, piece by piece. And that’s exactly what I did for the next year and a half. I rummaged around inside my mind, deciding which rules to keep and which ones to throw away.

Most of them turned out to be garbage anyway—rules I’d inherited without even knowing where they came from.

And once that clutter was gone, the light came rushing in. I emerged from that grief a new person. One who craved playful moments, fewer rules, deeper freedom.

And then I met Matt.

At first, I was drawn to his strength. He’s a good father, a hard-working man—the kind of traditional masculinity that stands resolute, that keeps his boots dirty and figures shit out.

Matt is steady. He’s reliable. But there was something else too—something about him that sucker-punched me, hit me square in the chin, and had me falling hard.

I caught glimpses of it early on—when Matt would turn on his jam music, roll the windows down on his truck, and dance while driving with a grin on his face. It wasn’t for me. It wasn’t for anyone. It was for himself.

Pure joy for the sake of joy.

Matt has a childlike spirit. His soul knows how to play. And rediscovering play with him has brought so much joy back into my world.

Last night, on a random Wednesday, we made a quick escape to Birmingham to catch a young jam band, Dogs in a Pile. They were playing at a small, funky venue called Saturn where the crowd was young, if a little bit fratty. We definitely aged the place up, which felt hilarious. But the music was wild, and it took us away.

About an hour into the night, a bouncer stopped by and said, “Hey, y’all are a cute couple. You look really happy together.”

It was a sweet and unexpected moment.

And honestly, I knew what he saw.

Because in a sea of bodies, it was clear who was dancing with freedom and who was dancing to be seen. Some moved with abandon, shaking out their bones and letting the music take them wherever it wanted.

Here’s the thing about jam music—it’s like life. Unpredictable. A song can last 30 minutes, shifting through five different tempos and styles before it finds its way back to the original melody. You never really know where it’s going.

For those trying to control the moment or perform it, that unpredictability is unnerving. They freeze, unsure what to do with their bodies. Some laugh awkwardly or throw in an exaggerated air guitar to diffuse the tension.

But those who lean into the chaos—the ones who close their eyes, feel the change, and let the music carry them—those are the ones who get it.

The bouncer saw it.

We were there to shake it out, and we loved every second of it. We danced until our bones ached, went back to the hotel, ate trashy chicken fingers, and slept like the dead.

My inner child was laughing at the top of her lungs when I fell asleep that night, like my soul had been swinging for hours.

And this is how I want to live.

This is how I want to leave this world.

Not as a tightly wound spring, exploding into the great unknown with the wasted energy of a thousand unrealized moments of joy.

I want to spend it all.

Every single bit of it.

At the end of this life, I want to crash into bed like I did on that random Wednesday night after a concert with my best friend—heart full, head buzzing with music, muscles thoroughly spent from dancing.

A life lived well.

That’s how I want to go.

Exhausted.

Happy.

Played out.

Whole.

Dear friends,

It means the world to me that you’re here. Fear often tells me to hold back, but sharing these pieces of my heart is my way of pushing past it, step by step.

I’ll always keep my words open and accessible because encouragement shouldn’t come with a pay wall.

For those of who volunteer your financial support, thank you for helping me continue this journey. Thank you for keeping the lights on, and most especially for showing up alongside me in this process of growth.

With love and gratitude,

Mary Katherine

I saw her comment. It made me feel sorry for her that she didn’t get it. She needs to grow up a bit.

Great message! I didn't realize that I am still closed in by rules until I read your article. I am 68. Hopefully this old dog can still learn some new tricks on the road to freedom.